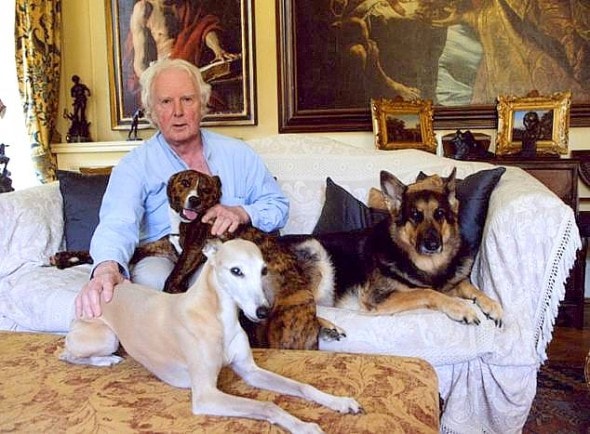

Renowned art critic Brian Sewell shares experiences of his life with dogs in the UK. We will be bringing his stories to you throughout the day – this is part 2. Parts 2 and 3 are excerpts from his book Sleeping with Dogs: A Peripheral Autobiography. Please bear in mind that pet customs vary across generations and countries. Female dogs are typically referred to as bitches, and for many years it was not common for people to spay or neuter their pets.

Life in Kensington Gardens during the Seventies was much as I remembered it from my pre-war childhood: serene, habitual, subtly changing only with the seasons.

Wild geese arrived and left, leaves budded and fell, and Londoners and visitors alike basked in the summer sun, although not always very peacefully if my six dogs were around.

They regarded sunbathers and courting couples as obstacles to be leapt over at speed. So when we arrived in the park one summer’s evening in 1972 and discovered too many people just within the gate, I decided to walk a little further before letting them run free. The resulting pulling and yelping attracted the attention of an elderly woman carrying two shopping bags.

‘I can help you to control your dogs,’ she said, with the air of one supremely confident that her interference would be welcomed.

‘I am perfectly in control,’ I responded, just as the dogs chose to change places from left to right, their leads crossing my arms behind the old dame’s back and encircling her in a tight embrace from which, her arms hanging straight to hold her shopping, she could not escape.

And there we were, nose to nose at first, then, as the dogs pulled harder, cheek to cheek, she walking very slowly backwards and me forward, praying that we would not topple.

Somehow I slipped the leads from my wrists and away ran the dogs, releasing her without accident — and not since Beatrix Potter’s Mrs Tiggy-Winkle scuttled naked away up the hill has any old lady vanished in so quick a trice.

Such incidents aside, I have always liked having dogs about me and never more so than when in bed, for a dog is infinitely more comforting than any hot water bottle. I have slept with all my dogs, one, two, three, or four at a time, waking, as I always do, with the not-quite dawn, but often making no attempt to leave my bed, so luxuriously seductive is the warmth on all sides.

For an hour or more I have lain in this cocoon at least ten thousand times, ignoring insistent thoughts of the working day, as immobilised by my companions as by anaesthesia. This, when the time comes, is how I wish to die.

It’s a pleasure I have enjoyed since my penniless childhood when bedrooms were grudgingly heated and the first five minutes between the sheets were spent shuddering with cold as they sapped the heat from one’s body — unless one had a dog.

My first was Prince, a black and white mongrel with pointer in him. A present for my third birthday, he was about a year old when, on July 15, 1934, he joined my mother and me at Ocean Cottage, a tiny hideaway in the fishing village of Whitstable on the North Kent coast.

My father, married to another woman but with a history of philandering, had taken a long lease on the place to lend privacy to his affair with my mother. He died before I was born and we had not tuppence to rub together.

It made no sense to add to our household a carnivorous animal that would eat as much as we did. But add him my mother did and my new playmate slept on my bed at night and joined me on the shingle beach by day.

His long tail whipped me as he wagged it and he was boisterous enough to knock me down before licking my face in affectionate apology. He would dash into the sea to retrieve great parcels of weed to be presented as a gift. But I recall only one misdemeanour, when he pulled a neighbour’s laundry from the line and, catching his head in some vast undergarment which combined vest and pants in one, found himself leaping up and down half-hanged and unable to detach his head.

For five years ours was an unquestioning brotherhood and I did not know how much I loved Prince until the day of our sudden parting. On the last day of August 1939, three days before the outbreak of World War II, my stepfather-to-be arrived at Ocean Cottage, announced that Whitstable would inevitably become a war zone and, watched by Prince, packed our baggage into the car, ready to depart to London.

The doors of the cottage locked and bolted, the windows secured, ‘Uncle’ Robert took Prince to the beach and shot him.

I did not see the deed, nor Prince’s corpse washed away by the tide, but I heard the shot and Robert’s return without my dog required no questioning from me. He was, of course, quite right;

London during the Blitz would have been no place for a dog. And on what, our rations near starvation level, could we have fed him? But I immediately developed a silent and unremitting hatred for Robert, despite his promises that I could have a dog when the war was over.

I held him to it. On May 8, 1945, we were allowed a day off school to join the jubilant crowds celebrating VE Day, but I cycled instead to North London, a round trip of about 20 miles, and paid five bob for a puppy called Penny, born to a mongrel terrier owned by a school friend.

Black and white like Prince, Penny was tiny enough when I got her to hold in my cupped hands. Despite meagre rations, including the unwanted gristle left over from our dreadful school meals, she grew up a tough and highly intelligent little dog able to understand a human vocabulary of 50 words or so.

It was impossible to discuss the French painter Poussin without her mistaking him for Puss and rushing to the window to bark at the supposed cat. And often, seemingly asleep, she reacted so oddly to our conversations that we asked ourselves what on earth we had just said, then realised that ‘walk’ or ‘biscuit’ had been part of the last sentence.

In the bitter winters of the later Forties, Penny slept in my bed, radiating the igloo, as it were, and cuddling her kept my front warm as toast, no matter how cold my back and far-off feet might be.

Her company made bearable the oppressive closeness of family holidays in Devon and on the Isle of Wight until, at 16, I could break free of them and stay at home, enjoying an extraordinary sense of both liberty and responsibility while my parents bickered in Brighton in an hotel they could barely afford.

When I joined the army for two years’ National Service, Penny pined and my mother could only walk her on the lead, for if she saw a soldier in uniform — then a common sight — she ran to him. That she could distinguish a soldier from a civilian suggests considerable intelligence.

Later, after studying at the Courtauld Institute of Art, I joined Christie’s as an ‘authority’ on old masters, and each day Penny and I walked briskly to and from their offices in Mayfair. There, her snoozing at my feet was interrupted by enthusiastic lunchtime dashes to Green Park, but over time the tireless Penny tired.

One wintry weekend early in 1960, we drove to my mother’s house at Castle Hedingham in Essex and I left them there together — ‘Two old bitches keeping company,’ as my mother put it. All was well until that June when Penny fell ill and, during exploratory surgery, the vet discovered that she was riddled with cancer and increased the anaesthetic to lethal level.

That evening, I drove the 70 miles to bury her, speechless with sorrow. She had been my closest companion for more than half my life, and I was quite unprepared for the emotional consequences of her death.

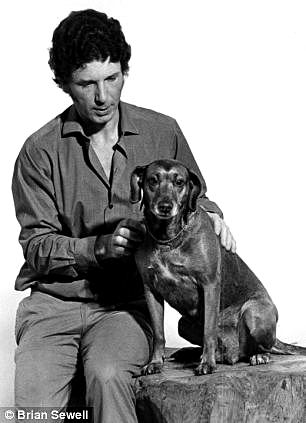

Any thoughts of getting another dog engendered so sharp a grief that I did nothing for three months. Then, on an errand to Harrods for my mother one Saturday morning, some impulse took me to their pet department where I caught sight of a lean and leggy pup, a brown pointer-whippet cross with long floppy ears.

When I picked her up, she sank her claws into my tie, an expensive thing of woven silk. There followed a pantomime in which the Harrods girl attempted to hold her still while I unhooked my tie, but this mid-air operation failed, so, having rummaged for a fiver in my pocket, I walked off with the pup still clinging to it.

That afternoon we drove to my mother’s for tea. Then three months old, the new pup leapt like an adult thoroughbred over Penny’s grave among the roses and, seeing resemblance between this new puppy and a girlfriend whose long hair and coat tails always seemed to stream in the wind as she ran for buses in Kensington High Street, I named her Susannah, Susie for short.

She adored my old Daimler coupé and in those days it was safe to leave it parked in London streets with the hood down and Susie at the wheel. On the move, she would lean against me on the bench front seat and watch the world go by — an intelligent and observant companion.

In the whole of her long life she never slept anywhere other than in my bed. We were inseparable and when she was nine, I received a phone call while in New York to say that she was desperately ill and needed a hysterectomy. I flew home on the first available plane.

This my mother held against me when she in turn fell ill. I was again in America, but this time I stayed where I was. I made amends on my return, sending her to George Pinker, one of the Queen’s surgeons (at vast expense), but for ever after, at the mere sniff of a cold, she reproached me with:

‘You came back for your dog, but refused to come back for me.’

Susie recovered with astonishing speed, but her gynaecological problems had disproved the old wives’ nonsense that every bitch should have at least one litter to prevent ‘women’s troubles in later life.’

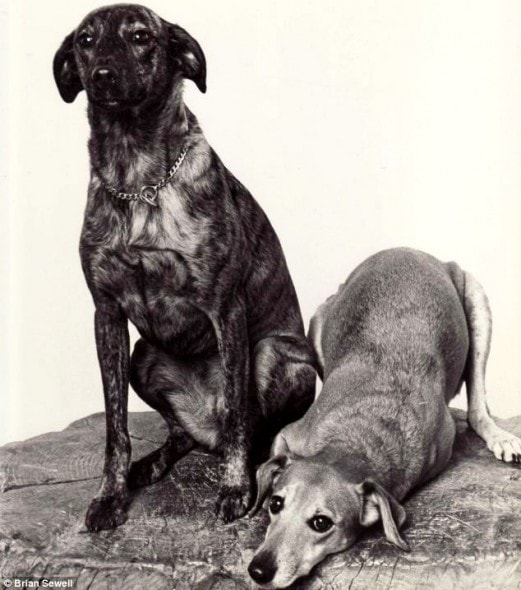

Aware of this, I had, several years previously, allowed her to be mated with a whippet called George. The result of what my mother insisted on calling their ‘wedding’ had been a litter of eight puppies. One was Ginny, at first my mother’s dog but later as much mine when, increasingly frail, my mother came to live with me.

Our household expanded still further when we were joined by Hecate, a blue whippet puppy much given to eating and drinking. With dinner guests installed in the dining room, Hecate would lick clean the glasses left in the sitting-room and would later be found asleep in an armchair, belly up, snoring on the dregs of whisky, gin and wine.

For all this, she proved a dutiful maiden aunt when, in the summer of 1970, Ginny produced a litter of six puppies. In this, she received no support from her own mother Susie, who for some reason seemed intent on harming them.

Understandably, Ginny became hysterically anxious if she sensed Susie anywhere near her brood, but Hecate was tolerated and would occasionally be allowed to shepherd a wanderer back to the basket or through the tangle of the garden.

We kept three of the puppies, calling them Schubert, Spinoza and Gamage, and, with Hecate’s help, Ginny educated them into adolescence. But pregnancy had exhausted her and she was old before her time.

Never again did she run for the sheer joy of it, or chase pigeons, squirrels and rabbits, and early in 1974 she was diagnosed with diabetes. The following March she quietly faded away.

In August 1975, two months after her 16th birthday and only a few months after we had lost Ginny,

Susie also appeared unwell. Leaving her with Rusty Williams, our local vet, I returned home after a day of preparations for a trip to Turkey to find a message from him.

Susie had died — died after sharing my bed for all those years, died on an operating table among unfamiliar smells and in the hands of strangers. I felt that I had failed her and the intensity of the loss prompted sudden recollections that for months caught me unawares with a welling tear and a catch in my throat.

In 1981, I lost Hecate to a devastating stroke and in 1986 all three of Susie’s grandchildren, all by then in double figures and with whitening whiskers. When Spinoza, the last of them, died in December that year, my misery was absolute.

It was not just for her that I mourned but for her sisters, her mother and grandmother, and for Hecate too. For more than a quarter of a century they had rampaged through all aspects of my life and I was unprepared for such emptiness and silence in the house.

Fortunately it did not last long for, as I will explain in Monday’s Mail, a phone call from Rusty the vet was about to bring yet more canine chaos into my life — this time in the form of a libidinous mongrel named Titian and his murderous companion Mrs Macbeth.

Hound That Sniffed Out Ghosts

When Susie was a year old I took her to Dartmoor where, at a ring of standing stones known as Grey Wethers, she sensed some presence that disturbed her — perhaps even a ghost.

I could see no reason for Susie’s risen hackles, her sudden flight and her refusal to slow down as, shouting, I ran after her. She stopped only when she blundered into a bog.

Nine years later, in 1972, we moved into a new house in Kensington and she again sensed something, on the stairs to the kitchen. Unable to run, she simply lowered her haunches, trembled and howled.

I too sensed something disagreeable — a chill and a stench through which I could pass in a stride, of much the same height and volume as a human being.

One evening, encountering it on the stairs, I sat and talked to it. I said had no way of remedying its misery. I wanted only that the house should be a happy place for me and my dogs.

Anyone witnessing this would have thought me mad, but, by coincidence no doubt, the column of cold and mortal stink disappeared, and never again was Susie so disquieted.

I have seen other instances of dogs seeming to possess a sixth sense. I’m sure my dogs have had an intuitive understanding of illness in human beings.

Hecate, my blue whippet, was responsible for a small miracle when an old friend named Margaret, struck dumb and paralysed by a stroke, languished in hospital. ‘We have made her comfortable,’ the Sister said, ‘but it’s only a matter of time.’

On my next visit I smuggled Hecate in under my overcoat, pretending to have a broken arm.

Margaret’s eyes widened, there was the faint hint of a smile, and for the first time since the stroke, she reached out, to touch the little dog — and Hecate, usually a wild wriggler, settled next to her.

We managed this a second day before being discovered by the Sister. But it mattered not, for we had brought about the miraculous first signs of Margaret’s recovery.

To read part 1, click here. To read part 3, click here.